|

Dating ancient

cultures has been one of the most demanding tasks of the

archeologists. The Indus Valley culture is estimated to have

flourished between 2500 to 1500 BC

(1)

but its origin is

unknown. The two most important cities of the Indus Valley are

Harappa and Mahenjo-Daro shown on the map of Chapter 16,

The South-West Expansion. This region is presently within

Pakistan but was once part of India. The root word “in”

forming both India and Indus means

descend in

Turkish, an appropriate selection for the name of a region

where central Asiatic Uighur tribes descended. In Latin, Old

German and in English “in” implies a similar meaning

indicating location or position within limits. Such root words

have their origin in the Proto-language of Central Asia and

should not be labeled as resulting from pure coincidence.

The Indus

civilization left behind a multitude of seal molds and tokens

made chiefly of steatite whose size are one to two inches

square. More than 60 sites have yielded seals and tokens of

stone, copper, silver, bone, terra-cotta, or ivory

(2). The

inscriptions on the tokens contain about 400 different

symbols, but scholars have few clues to their meaning. The

script on the tokens is still not deciphered, in spite of

claimed decipherments. The tokens contain several signs

similar to the ones found on the Jiroft brick. If the settlers

of the Indus Valley came from the north the logical conclusion

would be that the Jiroft script predates the Indus Valley

script, hence Jiroft script should be older and less

complicated than the Indus Valley script as well as the

Sumerian cuneiform script. Archeologists have found Indus

carnelian cylinders in Mesopotamian tombs. The earliest

textual evidence for direct contact between the Indus Valley

and the Sumerian culture of Mesopotamia dates from 2100 BC and

continues down to 1700 BC (3).

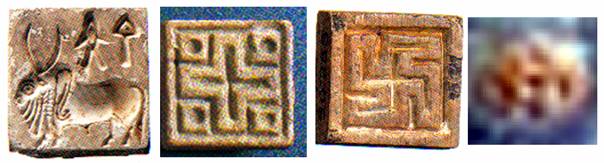

Below left a

handful of Indus Valley tokens and two interesting mold

examples are shown. The person on the central mold is seated

cross-legged in a typical oriental pose. His horned headdress

stands among some unknown signs. On the right we see a

mythical three-headed bull or zebu, a clear indication that

the Indus Valley culture worshiped horned animals (see Chapter

15, The Sacred Horn). Even today the cow is considered

to be holy in India.

The large

number of symbols on the tokens implies that the Indus Valley

script is most probably logographic. In order to certify that

the signs on the tokens display a linguistic structure a

statistical analysis has been recently carried out on the

frequency of occurrence of these signs

(4). The result clearly

demonstrated that the Indus Valley script is in good

correlation with several existing human languages. But the

script is not only seal based and logographic, but is also

pictographic. It can be considered to follow the same logic as

the Egyptian hieroglyphs. On the left token below we see a

zebu, above which a stylish human form and an arrow are

carved. The message of this seal can be interpreted as being

“the Okh leader” since both horned animals and

arrows are symbols of the Okh leader (see Chapter 12,

The

Anatolian Expansion).

The

second and third seal molds below are similar symbolic

representations of the Asiatic Uighur leadership, as discussed

in Chapter 6, Universal symbols. The four dots around

the + sign stand for the four corners of the world, implying

that the leader controls a vast region. It is interesting to

notice that a similar symbolism (four dots around a central

dot) is marked in brown on the thigh of the bull-man of the

Jiroft vase (see Chapter 16 the

South-West expansion).

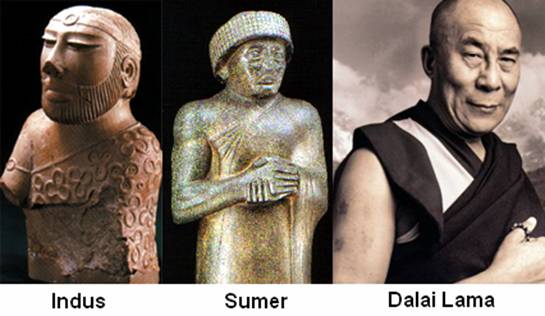

The

interaction between the Indus Valley and Southern Mesopotamia

can be noticed from different perspectives. An unexplored

perspective is the similarity between dressing styles. Below,

on the left we see the statue of an Indus Valley king and on

right the Sumerian king Gudea (2141 – 2080 BC). Both rulers

have their right arm uncovered and the manner they wear their

garment is quite similar. The same style of leaving the right

arm uncovered has been adopted by many Central Asiatic

religious leaders. Even today the spiritual leader of Tibet

is dressing in a similar manner.

A further

aspect to be noticed on the garment of the Indus Valley

“Shaman” King is the trefoils design. As mentioned in the

previous Chapters 10 and 14, there is a close relationship

between üç (the number three) and

uc (leader) as

well as uç (fly) in most Altaic languages. The

sculpture of the Indus Valley King may also have originally

worn a horned headdress (now missing) judging from the shape

of the back of the head. When such correlations are

complemented by the form of the eyes of the Indus Valley king,

the Asiatic origin of these people becomes most probable. |