|

The Hittites

who lived in central Anatolia during the second millennium BC

spoke a language which is accepted as the first Indo-European

language. However, the greater part of the Hittite vocabulary

is of non-Indo-European origin

(1). In Hittite the laryngeal

(guttural) sounds originated from the Asiatic Proto-language.

For example, the “kh” sound is found in many words and should

be pronounced as “Okh”. The name

Hittite was given to

this language by modern scholars as being the official

language of the

Land of Hatti;

but it should be pronounced as

Okh-At-ili. Since the

Hittite language was a monosyllabic language connected to the

Proto-language and to all Altaic languages, one should split

the words into its constituent phonemes. Okh means

“arrow”, At means “horse”

(2)

and “il” means

“The Land”, while “illi” means “from the land” or “belonging

to the land”, therefore Okh-At-illi or

Okh-At-ly

became Khattili => Hattili and finally Hittite. The suffix

“-ly” is still existing in Turkish meaning “mixed together”,

giving a further meaning to Okhatly “a mixture of Okh and At

people”. It is most probable that “At” and “As” were names

given to the same people originating from western Asia. We

find “At” and the suffix “-illi” in the name of the Hun leader

Atilla or Atilli.

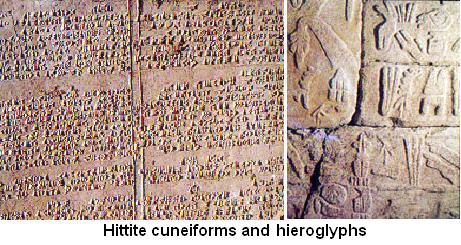

The Hittites

used two different scripts simultaneously. These were the

hieroglyphic and the cuneiform scripts. The cuneiform script

was adopted by the Hittites from the Accadians. This means

that there was a close relationship in both language and

culture between the Hittites and the Accadians. The name

Accad

becomes meaningful when split into its constituents Acc (Okh)

and Ad meaning “name”. We get from Och-At = Okh-Ad => Akhad =>

Accad the meaningful word “Okh name” a clear indication to the

Och people. The laryngeal “kh” changed in time and softened to

a double-c.

The

hieroglyphic script was mostly used to write in the Luwi

language and was the preferred script on monuments and seals.

The Luwi language is closely related to Hittite and is

mentioned as Luwili in Hittite texts. Luwili later on

transformed into Lycian, which became the language used by the

south-Anatolian Lycians of the classical epoch. Below left we

see a stele inscribed with the Hittite cuneiform script and on

the right a portion of a wall inscribed with hieroglyphic

script from Hattusas, Central Turkey

(3).

In order to

show the connection between Hittite and the Altaic languages

we need concrete examples obtained from written original

texts. There is a book published in 1980 by Ahmet Unal

discussing some Hittite phrases (4). We find many Sumerian

words in these sentences, which could either be borrowed from

the ancient Sumerian language of Mesopotamia or could also be

independently related to the Asiatic Proto-language. Here is

one example:

Dingir-lim

: My God. “Dingir” meaning “God” in Sumerian, already

discussed in chapter 22, Egyptian Deities. “-lim” is a

suffix still used in Turkish as a possessive pronoun.

Kililu = Gilim

: Wreath or Headdress. “Kyl” means “hair” or rather a single

thread of hair in Turkish. But “kylly” means “mixed with

threads of hair” (-ly is already mentioned above) and

therefore the Hittite word Kililu or Gilim is an appropriate

definition for a wreath worn on the head.

Lu-Sang-a:

To the holy priest. The first syllable stands for “holy” and

is found in Turkish as “ulu”, already mentioned in

Chapter 29, The bird symbolism. Sang means “respectful,

important person” and is found in Japanese as “san” and

in Turkish as “sayýn”. The same meaning is found in “saint”.

The suffix “-a” meaning “to the” is still used in Turkish.

Therefore, Lusanga means “to the saint”.

We see that

Hittite is an agglutinant language similar to Altaic languages

containing several suffixes still existing in modern Turkish.

Such a sentence formation is not found in most Indo-European

languages. These three words above are enough to explain an

original sentence obtained from a Hittite text:

DINGIR-LIM

GILIM-an-zi LU-SANGA-ya GILIM-an-zi,

which can be translated as: “They adorn the god with a wreath

and also the priest (saint) with a wreath”. The “-zi” suffix

makes the word definite, similar to the English “is” or the

German “ist”. In Turkish “iz” stands for the definite plural

similar to “we are”.

Without going

into further detail we can conclude that the Hittite language

forms a bridge between Altaic and western Indo-European

languages. The original connection between Hittite and

Sumerian can be traced back to the Proto-language of Asia from

which Turkish is the closest descendent. In order to be

convinced of such an ancient connection between Turkish and

Sumerian here is a short list of Sumerian words. The Turkish

equivalent is given in red and in brackets.

Father:

Adda (ata,

baba), Mother:

Ama (anne, ana),

Lord: Aga (agha),

Horizon: An (tan),

Male: Ar(er),

First: As (as),

God: Dingir (Tengri),

House: E (ev),

Shore: Kýya (kýyý),

Blow: Es (es),

Fat: Gisko (shishko),

Upright: Dim (dik),

Arm: Kol (kol),

Sleep: Uiku (Uyku),

Bird: Kus (kush),

Right side: Sag (sað),

Oak: Mesu (meshe),

Sheepfold: Ag (agýl),

Large: En (en,

engin), Come:

Ge (gel),

Blood: Ka (kan),

Canal/Blood vessel: Kanal (kan

damar), Say:

De (de,

demek), Stop:

Duru (dur),

Settle: Kur (kur,

kurgan),

Run: Kusu (kosh),

Smile: Güles (gülech),

Bore: Bur (burgu),

Ax: Bal (balta),

Shine: Bar (barla/parla),

String/Rope: Ýb (ip),

Pretty: Alým (alýmlý),

Holy: Ulu (ulu),

Separate: Kup (kop),

Who: Gim (kim),

Soldier: Ir (er),

Wood: Odun (odun/ot-un)

These 37 words

form a small but important sample showing that even after

almost 5,000 years we can still find common words between

Turkish and Sumerian, containing the same sound and the same

meaning (5).

Turning our

attention to the Sumerian architecture, we see that people

living on the flat prairies of Mesopotamia built stepped

pyramids called ziggurats. They built these high structures as

symbols replacing the mountains which lacked in their region.

We saw that this wish for high-rise architecture existed also

among the Maya and the Egyptians. The common architectural

designs are another sign of their common origin. Not only the

Sumerians, but also the Elamites who lived in south-western

Iran built ziggurats (see Chapter 18, Towards Sumer and Elam).

Below-left we

see the Sumerian ziggurat near Ur and the Elamite ziggurat

presently in Khuzestan, Choghazanbil - Western Iran. Khuzestan

is the region of Iran bordering Mesopotamia. This name is

clearly Ghuz-istan originally being Oghuz-istan or

Oghuz-land, clearly indicating that the ziggurat

structures were built by the Och people. Oguz means “we are

the Och” (see Chapter 2,

Diversification of languages).

|

|

References

(1)

The Hittites, O. R. Gurney, Pinguin Books, page 119,

1976, England.

(2)

See Chapter 12, The Anatolian expansion.

(3)

Atlas Magazine (in Turkish), Jurgen Seeher, May 1999,

page 88.

(4)

Hitit Sarayindaki Entrikalar Hakkinda Bir Fal Metni, A.

Unal, Ankara University Publication, No: 343, page 82, 1983,

Ankara,

Turkey.

(5)

Sumer ve Turk Dillerinin Tarihi Ilgisi, Osman Nedim

Tuna, TDK Yayinlari, No: 561, 1990, Ankara, Turkey.

|